📄 FBI Files on Kevin Mitnick:

https://vault.fbi.gov/kevin-mitnick/kevin-mitnick-part-01-final/view

Curiosity, Ethics, and the Lessons of a Hacker Mindset

When the FBI released its final case files on Kevin Mitnick, I found myself reading through pages of wiretap transcripts, investigative reports, and surveillance logs. Documents that once sat behind layers of classification. These reports outline the extent to which Mitnick relied not on cutting-edge exploits, but on human psychology. Convincing people to hand over credentials, exploiting trust in systems that weren’t built to anticipate deception.

It reminded me of reading The Art of Deception for the first time as a teenager, when my older brother handed it to me and said:

"You’ll like this—it's not about computers, it’s about how people think."

My teenage years were shaped by a deep curiosity about technology and security, but also by the values instilled in me. Values that ensured my fascination remained ethical. I wasn’t just interested in how things worked; I wanted to understand why they were designed that way and where the weaknesses lay. Understanding, not exploitation, was always my goal.

My Father, My Oldest Brother, and the Evolution of Telephony

My father worked for the General Post Office (GPO), later BT, and he understood telecommunications at a level most people never considered.

As a child, I absorbed his explanations about the evolution of the UK phone system. He would talk about pulse dialing and how it was replaced by tone dialing, explaining how rotary phones sent pulsed electrical signals, physically stepping through selectors in the exchange.

He'd rapidly make a “Dub, dub, dub, dub,” sound, mimicking the pulse for the number four, “Dub,” for the number one, “Dub, dub, dub,” for three: feeding the fingers of both his hands together like an inversed double helix in rhythm explaining the physical fingers like mechanical contacts in the oldest exchanges. That rhythmic pulse, once a mechanical necessity, eventually converted and 'upgraded' into the standard tone-based dialling system we all recognise today.

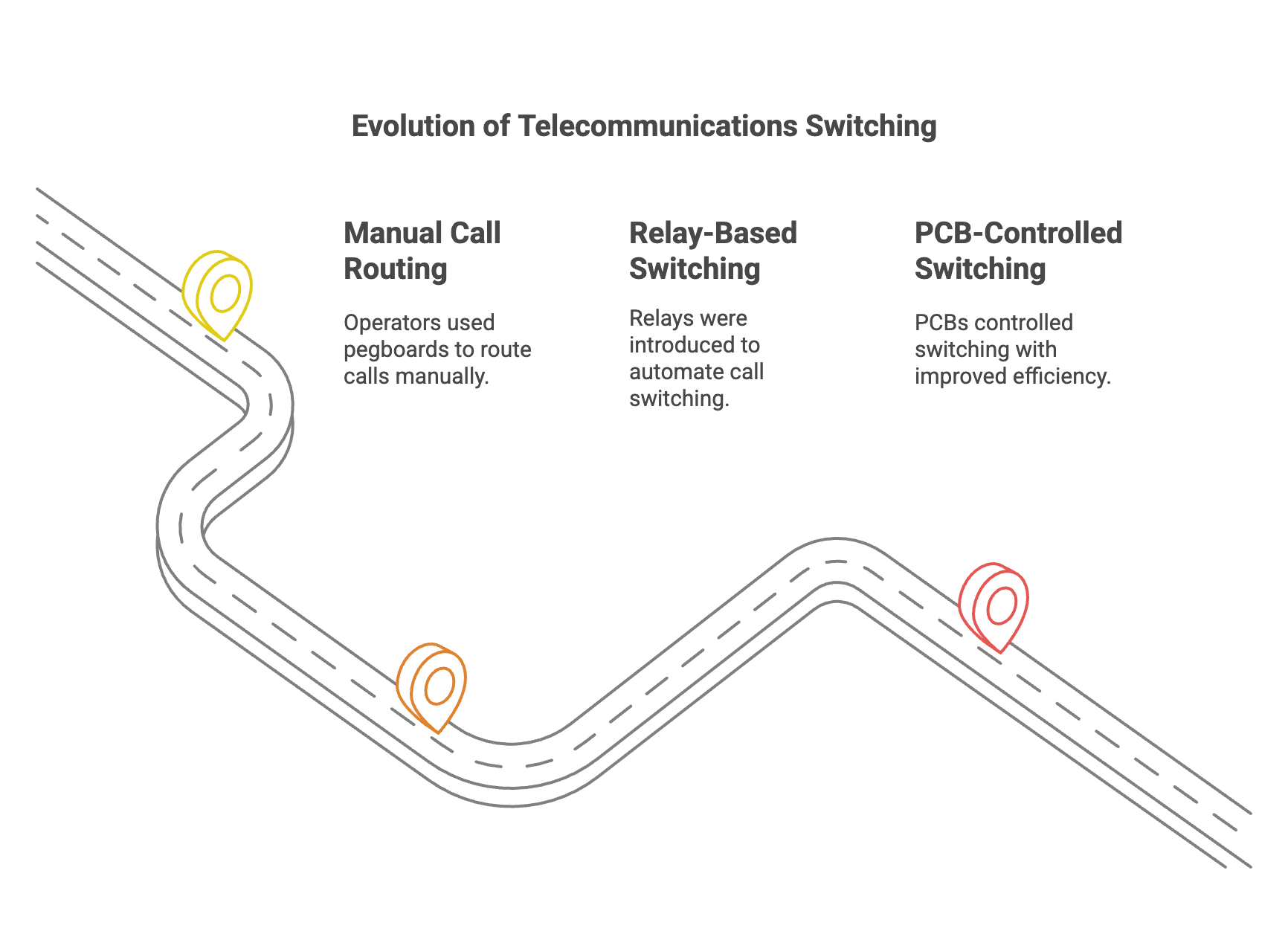

Before these electronic exchanges, calls were manually routed by operators using pegboards, and later, relays and flux-covered, resin-potted PCBs controlled switching. Primitive by today’s standards, but foundational to how telecommunications evolved.

Now, with Openreach actively stripping out copper lines across the UK, the era of analogue calls is disappearing entirely, replaced by VoIP and software-defined networks.

Growing up in a house where telecom tools, CB radios, and punch-down kits were everyday objects, I had an unusual advantage in understanding how these systems functioned. It wasn’t theoretical. I could see the physical infrastructure behind the phone system.

So when I first started reading about phreaking, blue boxes, and 2600Hz tones, it wasn’t abstract. It was an extension of what my father had already taught me.

A Teenage Fascination with Phreaking and Security

By the mid-90s, the internet was becoming accessible to ordinary households, and with it came endless information on hacking, phreaking, and security loopholes. We had the internet at home sometime around 1995-6, and free access was offered in college too.

I spent hours reading about early phone phreaks like Captain Crunch, who discovered that a plastic whistle from a cereal box could perfectly emulate a 2600Hz tone and manipulate AT&T’s long-distance networks.

I was fascinated by war dialling programs that would methodically scan phone numbers to locate modems, much like modern rainbow hash table generators brute-force password authentication today.

I feel a soluble memory of downloading a war dialler on Windows 95, but never running it. There was a point where curiosity and action diverged, and I always stopped short of crossing into grey areas.

My father had a habit of keeping things orderly, and that extended to our household phone system. He had a simple wooden box where my older siblings had to deposit money for every phone call.

It wasn’t just a practical way to cover costs—it was an unintentional security measure. If I had run thousands of automated dials looking for modems, the consequences would have been immediate and difficult to explain. Even at that age, I understood the risk vs. reward equation, and it made me appreciate the implications of unchecked exploration.

At the same time, my eldest brother introduced me to Kevin Mitnick’s books, and that solidified an important lesson:

Security wasn’t just about the technology.

It was about people—their assumptions, their trust, their willingness to believe a well-told lie.

Seeing Mitnick Through FBI Files vs. Hacker Culture

Revisiting Mitnick’s story through the lens of official FBI reports rather than his own books was an interesting shift. The files, now available to the public, document a relentless pursuit spanning years.

📄 Read the Files Here:

🔗 https://vault.fbi.gov/kevin-mitnick/kevin-mitnick-part-01-final/view

Phone traces, wiretaps, stakeouts—law enforcement treated him as one of the most dangerous cybercriminals of his time.

Hacker News recently had a lively discussion about this, with some arguing that Mitnick’s reputation was inflated by law enforcement, while others noted that his success wasn’t about deep technical exploits, but rather about persistence and social engineering.

"Mitnick didn’t really code at all. He was an intrusion specialist."

"He shook door handles until something opened."

"Reading his book, you get the sense that half of it might be made up."

These comments reflect something I noticed, too, even as a teenager. Mitnick’s legend was built as much on perception as on technical ability. That’s not to say he wasn’t skilled, but he was more con artist than coder. The FBI files make that clear.

I saw this in another story, a fictional portrait; the film Hackers, which depicted the FBI vs. hacker culture in full technicolour.

It was pure Hollywood, but beneath the stylised graphics and techno soundtrack, it captured something real:

The tension between institutional power and individual curiosity.

The battle between rigid systems and those who sought to explore their limits.

While the real Mitnick case was more about phone traces and social engineering than high-speed rollerblading through cyberspace, Hackers reflected the sense of adventure and defiance that resonated with a generation growing up alongside the internet.

Parallels to Modern Security and Cracking Techniques

Looking back at phreaking, war dialling, and Mitnick’s exploits, it’s remarkable how the core principles of security remain unchanged.

Social Engineering → Credential Harvesting via Phishing

Mitnick relied on calling IT staff and tricking them into revealing credentials.

Today, attackers use phishing emails, deepfake voice calls, and AI-generated scams to achieve the same result.

War Dialling → Network Reconnaissance and WiFi Wardriving

Scanning for weaknesses hasn’t changed.

War diallers searched for modems, while today’s equivalent is scanning open WiFi networks or unsecured IoT devices.

Phone System Exploits → VoIP and SIP Attacks

The shift from copper lines to VoIP-based telecoms has opened new vulnerabilities, including:

SIP fraud, VoIP DDoS attacks, and toll fraud schemes.

From Teen Curiosity to Enterprise Security

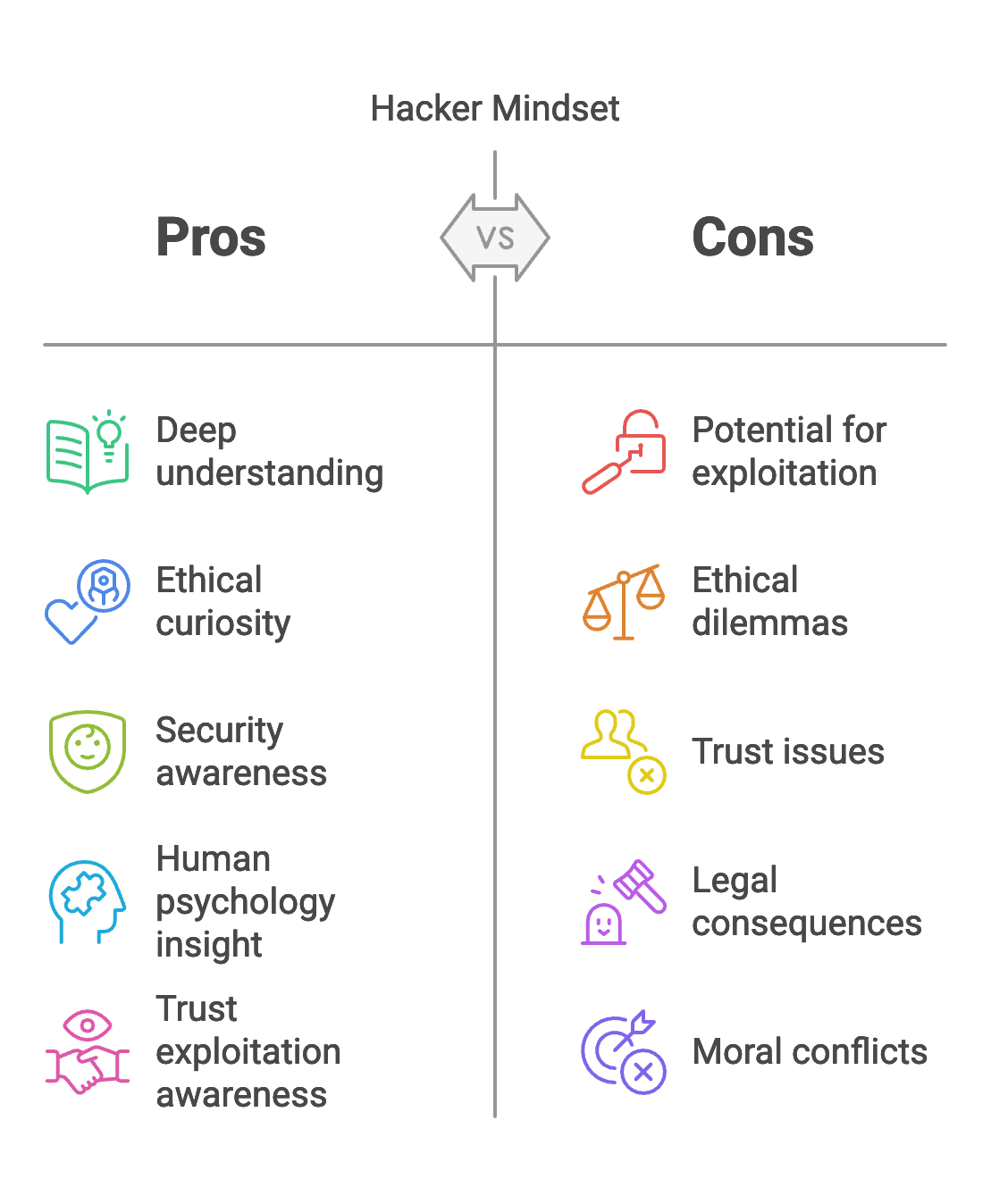

I don’t describe myself as a hacker, but the mindset; the drive to understand, to question, to find the flaws before they can be exploited, still shapes everything I do.

Curiosity is essential, but it must be balanced with responsibility, ethics, and a deep respect for the systems we build and the people who rely on them.